The Philippines will have its general elections this May 2022, along with other governments such as South Korea, India and Germany. Elections, or the process of selecting leaders to represent the interests of its citizens in policy-making and public administration, are a central institution in democratic governments. A truly democratic election’s end goal is to establish a representative government which focuses on the protection and promotion of its citizens’ rights, interest, and welfare.

Elections and public sector productivity

The administration of elections can be considered as a public service catering to its citizen’s right to vote. Thus, like other public services, it is a fruitful exercise to periodically re-evaluate its efficiency and effectiveness, as well as explore ways to improve it — much more in a service so crucial to good governance, and consequently, to a productive public sector.

This article presents different practices in the conduct of government elections, in an attempt to stimulate re-evaluation and a possible re-thinking of our current election-related practices.

A Framework for Evaluating Productivity

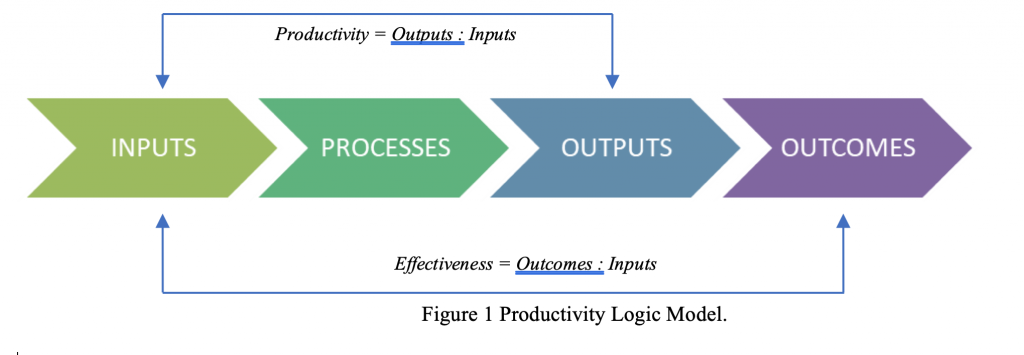

Before we present different electoral practices, it would be beneficial to start with a definition of productivity, as well as a framework which will guide us in our exploration.

Productivity is usually explained in the context of organizations producing a product or a service paid for by clients; technically, it is the rate of outputs per unit of input. Putting it in the context of the public sector, it is efficiently using public resources (i.e. tax paid by citizens) in producing quality outputs (i.e. policies and public services). Public sector productivity is about doing more with less, producing quality outputs, restoring public trust, and fostering good governance.

Productivity can be broken down into these components: Input, Process, Output, and Outcome. Analyzing productivity boils down to looking at each of these components, in relation to how they all contribute to the whole process.

In the case of administration of elections, a lot of factors are to be considered. The government uses public funds (input) to provide electoral services to its citizens (process) in order to have a set of newly elected officials, or sometimes, a public decision on a policy (output). The desired outcomes of elections could be an increased trust in the government, more representative policies, leading to better citizen participation, a more competitive business environment, and an over-all better performing economy — the list goes on. It is fair to say that there is a strong relation between the efficiency of the election process and the increase of public trust in the government and its institutions. In this article, we would try to explore the electoral process by looking at different practices classified under 4 different themes: voter registration, scheduling of voting date, accessibility of polling stations, and means of voting. For the purposes of this article, we will be dealing with the relation of these elements to an output indicator: voter turnout. While voter turnout is not an all-encompassing indicator to determine the efficiency and effectiveness of the electoral process, it can serve as a proxy measure.

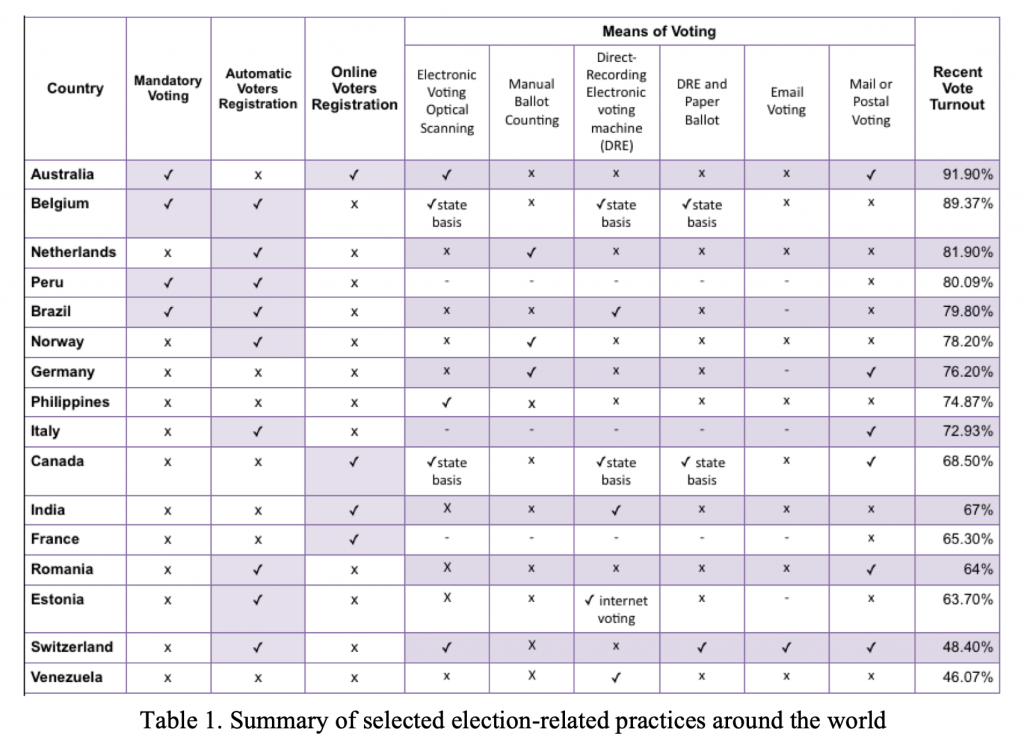

Here are some election-related practices around the world:

Voter Registration. Citizens are compulsory to vote in 22 countries in order to increase voter turnout. Non-voters are penalized in some countries such as in Australia and Singapore. In Australia, non-voters are notified by the government through email, text message, and snail mail seeking an explanation for non-participation in the election. If non-voters have no valid reason, they will be fined $20 for first time offense while $50 for succeeding offense. Also, the government can suspend the driver’s license of non-voters who did not respond to the notice or did not pay the fine. In Singapore, non-voters are removed from the certified register of electors of the electoral divisions in their area but their names can be restored by submitting an application to the registration officer with valid reasons for not voting, such as working overseas (including being on a business trip), studying overseas, living with their spouse overseas; overseas vacation; and illness or delivering a baby. A penalty of $50 will be imposed to non-voters if no valid reasons were presented. Nowadays, governments in some countries such as Italy, Norway, Romania, South Korea, Switzerland, Belgium, and Sweden linked voter registration with their national database (e.g. civil registry) hence, eliminating the need to register for the elections. In South Korea, the list of voters is linked with the national ID database which is updated periodically while qualified citizens registered in the public census are automatically eligible to vote in Norway.

Other countries such as Canada and France initiated multiple options for registration to make it easier and more convenient for their citizens. In Canada, citizens can opt to register online or on the election day itself. In France, citizens can register in person at their local town hall, through mail, online, or by sending a third party to deliver their application to their town halls. Before election day, countries like Norway, Germany, and Belgium send election details to their citizens to prevent unnecessary hassle in the precincts. In Norway, they receive a notification card stating the election time, date, and the location of their polling station. In Switzerland, voting papers, including polling card or voter identification card will be mailed at least three weeks before election day.

Scheduling of voting date. The schedule of the election also affects voter turnout. In countries like Australia, Belgium, Brazil, France, Germany, and Peru, elections are held on weekends so that working people have time to vote. Advanced voting is usually conducted for absentee voting – voters who are away from the area (e.g. employment) or are confined to institutions through illness or disability; but in some countries just like Estonia, Canada, Sweden, and Norway, advanced voting is applicable for all citizens. Norway is considered as the country with the longest advanced voting period which takes place for maximum of six weeks before the actual election day. The municipalities receive the advanced votes and they decide on the location and dates of election. In the case of Estonia, 7-10 days before election day, at least one polling place in every country center is open where citizens can vote regardless of their voting district of residence; all polling stations are then opened 4-6 days before the election. In Canada, advanced polls are held every 10th to the 7th day before the election day; in Sweden, citizens can vote in advanced at any voting location, 18 days before the elections.

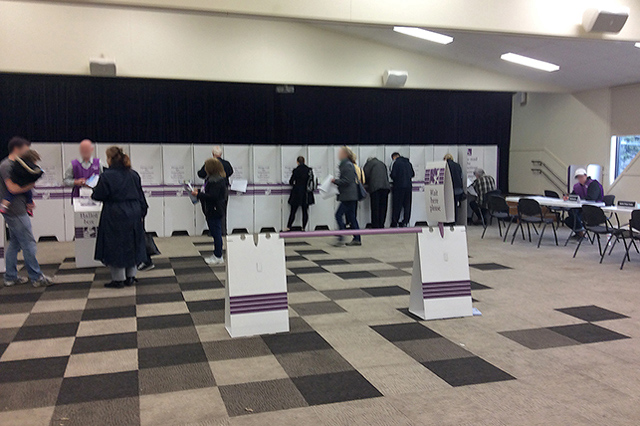

Accessibility of polling station. The accessibility of the polling station can affect the turnout of voters as well. India is considered to have the world’s biggest election, hence, the government mapped out the location of polling stations to make it accessible for the citizens living in far-flung areas such as those located in the forests and mountains. According to the Election Commission of India guidelines, a polling station must be less than 2km from a voter. In the case of Australia, citizens can vote at any polling place in their home state or territory while citizens in another state or territory can vote in their interstate voting centers.

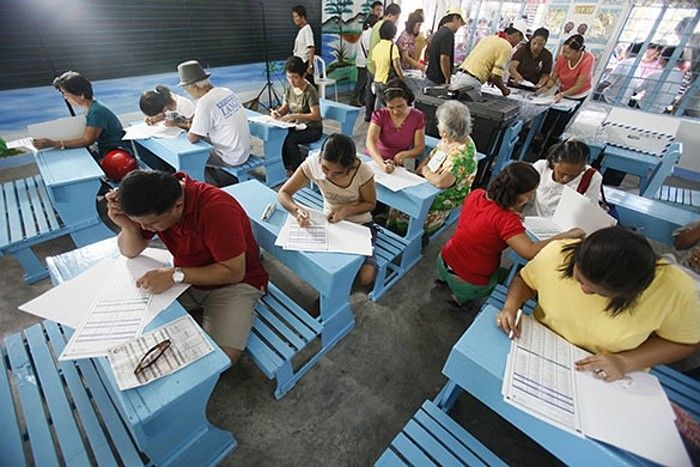

Means of voting. Many countries already shifted from paper voting to electronic voting because of its efficiency. There are different types of electronic voting: Optical Ballot Scanning Machine (Philippines), Direct-Recording Electronic Voting Machine (India and Venezuela), and Internet Voting (Estonia).

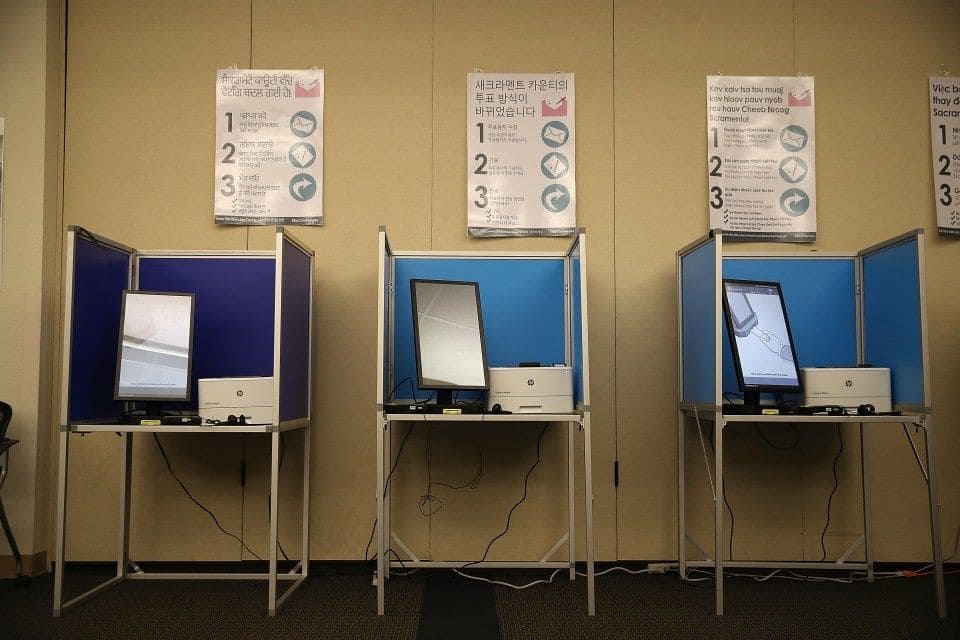

One type of electronic voting is optical ballot scanning that reads and scans marked ballot papers. The voting machine releases ballot receipt after reading the voters ballot which serves as their tangible record. In addition, it can also store voting data through memory card or upload the data then, connect through internet access. The Philippines started to use this type in 2010. Another type is the direct-recording electronic voting machines that records votes through computer hardware such as buttons and touch screen output. The machine produces a tabulation of the voting data stored in a removable memory component and/or as printed copy. One of its advantages is that it can be used as advanced voting device in polling stations.

The last type of electronic voting is internet voting, considered as more radical departure from tradition methods, refers to the use of the Internet to cast and transmit the vote. It can take various forms depending on whether it is used in uncontrolled environments such as remote internet voting, polling site internet voting, or kiosk voting. With remote internet voting, neither the client machines nor the physical environment are under the control of election officials. Voters can cast their vote anywhere (at home, at the workplace, at public Internet terminals etc.). This type of e-voting has an advantages such as reduced costs and greater convenience, cutting the time spent for voting ritual, increased political participation and turnout, and opportunities for innovation. However, it also has downsides such as security risks, digital divide, insufficient transparency, unsecured built systems, and insecure software downloads. In 2005, Estonia became the first country in the world to adopt internet voting. The i-Voting system allows citizens to vote at their convenience because the ballot can be cast anywhere with internet connection. The system only takes 3 minutes and brings votes from all over the world. It is being used only during advanced voting, from the 10th until the 4th day before election day. The system allows re-vote or repeated voting but only the last vote cast will count. Some countries employ several voting processes in order to accommodate all its citizens and increase voter turnout. In Canada, one can vote through paper voting, mail voting, mobile voting for seniors and persons with physical disabilities, and voting at home with the presence of an election officer and a witness for special cases. In Australia, citizens can vote through paper voting at any polling place in their home state (inter-state voting), electronic voting machine, mobile voting for sick people in hospitals, nursing homes, prisons and remote areas, and telephone voting for people who are blind or having low vision. In Belgium, aside from voting in person and by post, some citizens can vote by proxy where citizens can appoint someone to vote on their behalf. Citizens who have illness, business reasons, residents on holiday outside Belgium, students involved in examinations, those with religious convictions, and prisoners are qualified to use the said process to vote.

Citizen-centered Elections. By eliminating the usual roadblocks such as limited access to a specified voting precinct, limited availability of time to vote, limitations on mobility due to physical disabilities and restrictions, these election-related practices aim to increase voter turnout by making the elections more citizen-centric.

However, as the table above would show, a particular practice does not guarantee a high voter turnout rate. While Australia and Belgium may have benefited from its mandatory voting policy, Netherlands, which does not implement the same rule also have a high voter turnout. The top countries in voter turnout rate do not use electronic means of voting either. It is important to bear in mind that each country has its own context, and what works in another may not work in another.

Investing in Democratic Institutions. Aside from electoral participation rate, some of the other issues to be considered are the extent by which citizens actually feel that their vote counts, as well as their confidence in the integrity of the election results. While it is a good aim to make the whole process more convenient for the citizens, governments also need to work in strengthening its institutions. It all boils down to one thing: public trust.

Falun, a city in Sweden, works on increasing its citizen’s trust in public institutions by encouraging active citizenship. Swedish government works year-round to engage its citizens to make them know and use their rights, not just during election season. For example, they have developed a Democracy passport – with the size and shape of a national passport, it describes all the political powers of its citizens and all the forums where they have the right to weigh in, at the city, state, country, and European level. Other programs such as opening a Democracy center, which is a free space for democratic education and dialogue, as well as having a full-time Democracy Navigator to assist individuals and groups to make their voices heard, all help send a message to the citizens: that they are not just consumers of programs but are direct participants in the community. This sense of being involved has generated significant trust in their public institutions; thus, when election season comes, citizens have an active awareness to participate. We could learn a thing or two from this Swedish city by not only working on the efficiency and convenience of the electoral process, but by investing more in democratic infrastructure. And perhaps that’s the feature that sets the electoral process apart from all other public services – unless trust is the bedrock, that’s the only time when productivity will matter. And when productivity sprouts, trust becomes a by-product. The cycle goes on.