“The only way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas.†– Winston Churchill

The concept of the employee suggestion scheme (ESS) is quite simple. Employees are encouraged to share creative ideas for improvement and innovation in the organization. Through the ESS, two-way communication between the employees and the management is established. This increases the productivity and consequently improves the quality of products and services of the organization.

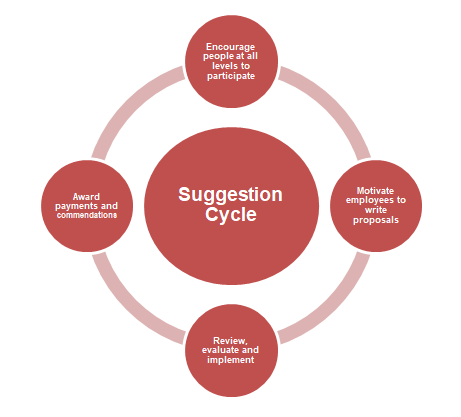

Acceptable suggestions can be on improvements in own work or of the entire working environment, savings in energy, labor, materials and other resources, improvement in processes and practices, improvement on tools and equipment, and improvement in safety. On the other hand, company policies, compensation and benefits, disputes, and criticisms are out of the scope of an ESS. There are two types of employee suggestion scheme: traditional (top down approach) and kaizen teian (bottom up approach). The traditional way involves soliciting suggestions with high impact and giving rewards to employees who contributed to increased financial performance of the organization. Meanwhile, kaizen teian which literally means “improvement proposal†focuses on small, incremental and continuous improvements. Implementing ESS, however, involves more than just putting up a suggestion box and waiting for employees to drop-in their suggestions. An ESS usually consists of four major components:

- Encouraging people at all levels to participate – From the head of the organization to front line employees, each member’s role is crucial to the growth of the organization.

- Motivate employees to write proposals – Employees should be empowered to submit proposals regardless of their position in the organization. Every suggestion must be fairly reviewed and evaluated.

- Review, evaluate and implement – Identifying who should evaluate the proposals is a critical step. It is not recommended to make the direct supervisor the evaluators of ESS because it might be biased. What most organizations do is to create a committee who reviews the proposals, make decisions on which suggestions should be adopted, and inform the employees of the results of their suggestions.

- Award payments and/or commendations – Will you give cash incentives for a helpful suggestion? Cash rewards may be effective but there are also other types of incentive such as vouchers, paid holidays, merchandise (watches, t-shirts, jackets, etc.) Regardless of what type of incentive it will be, it should be enough to encourage the employees to contribute towards productivity and innovation.Successful implementation of an ESS highlights a culture committed to building collaboration, teamwork and worker empowerment by focusing people. To guarantee the success of an ESS, the following factors have to be considered:

- Obtaining the management buy-in;

- Forming an ESS committee, and defining its roles and functions;

- Defining the suggestion process;

- Promoting the suggestion system to all employees; and,

- Establishing an evaluation and awards systems.