Despite the difficulties arising from the current pandemic, frontline government agencies and offices can aim for better frontline service delivery using actual feedback from citizens nationwide.

Using the results of the national survey conducted by the Development Academy of the Philippines (DAP) under the initiative of the Government Quality Management Program, government agencies and offices can focus on improving frontline service delivery using the key drivers of citizen satisfaction captured in the e-survey conducted in December 2020.

Aiming for quality service delivery that follows these key drivers or service attributes that have the biggest impact on citizen satisfaction will contribute to better transaction experience during the so-called “new normal.â€

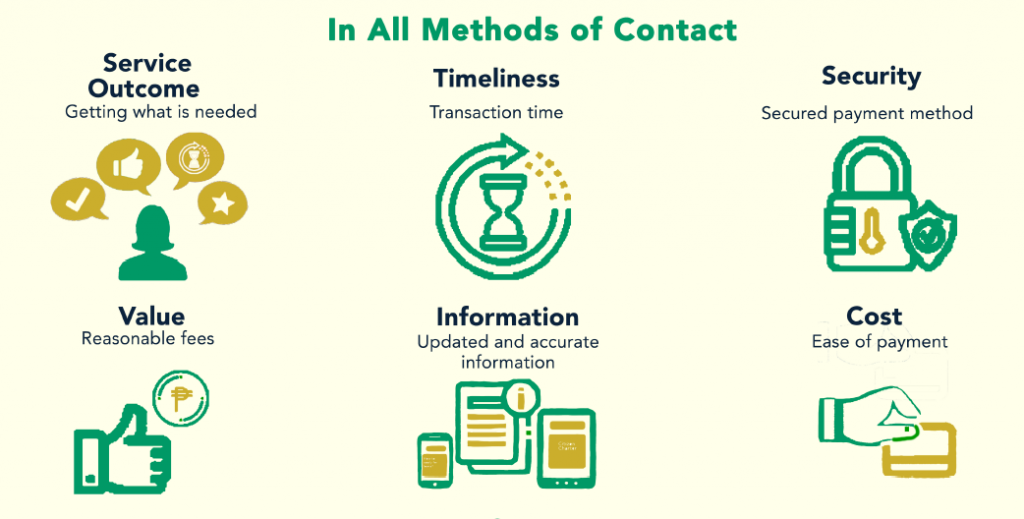

According to the DAP national Citizen Satisfaction e-Survey or e-CitSat, the key drivers of citizen satisfaction in all methods of contact, that is, for face-to-face, phone call, or online transactions are:

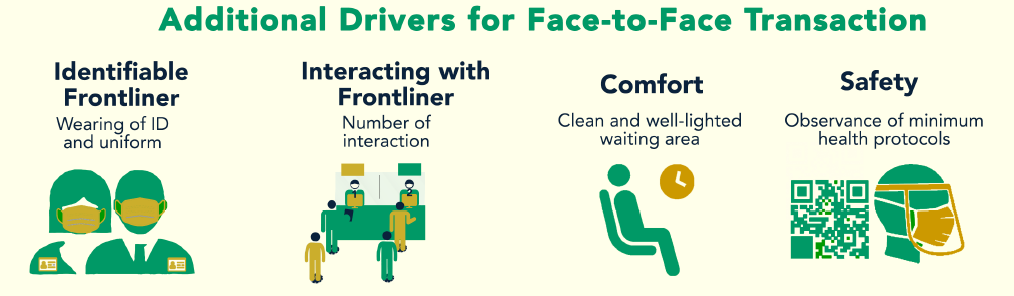

Meanwhile, for face-to-face transactions, there are additional service attributes that can contribute to a pleasant experience for citizens when they go to frontline government service facilities, especially with movement restrictions and health and safety protocols in place.

According to the survey, citizens appreciate frontliners wearing of IDs and uniform. This gives assurance that they are dealing with authorized personnel and not with fixers. Moreover, citizens would like to have fewer number of interactions with frontliners until their transaction is completed, especially during this time of the pandemic.

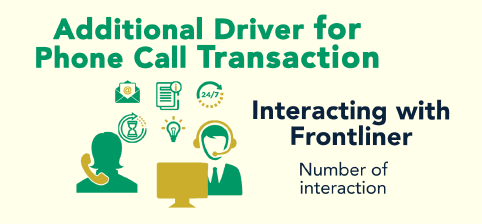

Likewise, for phone call method of inquiring or getting frontline government service, citizens would also appreciate having fewer number of interactions with frontliners when they make a phone call at a frontline government service office. Too many phone calls or being passed on to multiple staffs would contribute to dissatisfaction.

In the “new normal†where it is safer both for citizens and frontliners to interact using online method, frontline government agencies and offices will do well continuing or improving on another attribute of service. Citizens will be satisfied with the online frontline service delivery if they can easily navigate the government website.

When these key drivers of citizen satisfaction are considered in improving frontline government service delivery, citizens service experience may fare better resulting in smooth engagement on the part of both the frontline staffs and transacting citizens.

Professor D. Brian Marson, co-founder and senior fellow of the Institute for

Citizen-Centred Service in Canada pointed out in his lecture in DAP on “The Role of Service Quality Standards in Achieving High Levels of Client Satisfaction with Public Sector Services†that it is important to know the key drivers of citizen satisfaction to improve service. He called this the “outside-in†approach to improving service delivery.

Likewise, DAP Vice President Arnel D. Abanto underscored the value of evidence-based information. He explained that if you want to improve quality, you have to measure it. If you do not measure it, you cannot trace or monitor its improvement.

The key drivers of citizen satisfaction is just one set of attributes that can be measured and monitored in aid of service quality improvement.

Knowing what citizens like most in frontline service especially in critical times such as the ongoing pandemic, government agencies and offices have valuable information that can help them in their efforts to improve their services. With improved services, citizen satisfaction may be enhanced and, more importantly, contribute to the national goal of ensuring responsive, people-centered, technology-enabled, and clean governance.

The DAP seeks to empower leaders, strengthen institutions, and build the nation through pioneering, value adding, synergistic ideas, concepts, principles, techniques, and technologies addressing development problems of local, national, and international significance. DAP–PDC offers capability building, technical assistance, and research related to productivity and quality improvement. For more information, visit www.dap.edu.ph, email pdc.pdro@dap.edu.ph or call 0977-826â€3077.

This article was originally posted in http://pdc.dap.edu.ph/index.php/dap-survey-captures-key-drivers-of-citizen-satisfaction-in-frontline-government-service-during-pandemic/